1) "Under This Unbroken Sky" by Shandi Mitchell

Canadian screenwriter Mitchell’s fiction debut tells the grimly tragic story of Ukrainian immigrants who have left the steppes for the vast, unforgiving Canadian prairie.

In the spring of 1938, Theo Mykolayenko returns to his family after 20 months in prison. He’s been confined for his failure to pay an $11-dollar debt, and his governmental creditors also seized his house, his barn, his tools and, three weeks before harvest, his fields of ripening grain, worth $70. But Theo is a man of fierce will and work habits. Before his stint in jail, he had already survived all sorts of miseries and privations back home, then 23 days in filthy steerage and 3 years of struggle to establish his crop. He rejoins his wife Maria, their five young children (ages 5 to13) and his sister Anna, all of whom have strived mightily to subsist in his absence, and they start over. But just when hope and the possibility of happiness sprout again in this inhospitable climate, Anna’s cruel and conniving husband Stefan returns. His machinations lead them inexorably back toward tragedy—worse this time because it’s caused not by unscrupulous outsiders, lenders or government bureaucrats, but by kinfolk.

Not much style or literary finesse, but the family’s plight is affecting.

2) "Room" by Emma Donoghue

Talented, versatile Donoghue (The Sealed Letter, 2008, etc.) relates a searing tale of survival and recovery, in the voice of a five-year-old boy.

Jack has never known a life beyond Room. His Ma gave birth to him on Rug; the stains are still there. At night, he has to stay in Wardrobe when Old Nick comes to visit. Still, he and Ma have a comfortable routine, with daily activities like Phys Ed and Laundry. Jack knows how to read and do math, but has no idea the images he sees on the television represent a real world. We gradually learn that Ma (we never know her name) was abducted and imprisoned in a backyard shed when she was 19; her captor brings them food and other necessities, but he’s capricious. An ugly incident after Jack attracts Old Nick’s unwelcome attention renews Ma’s determination to liberate herself and her son; the book’s first half climaxes with a nail-biting escape. Donoghue brilliantly shows mother and son grappling with very different issues as they adjust to freedom. “In Room I was safe and Outside is the scary,” Jack thinks, unnerved by new things like showers, grass and window shades. He clings to the familiar objects rescued from Room (their abuser has been found), while Ma flinches at these physical reminders of her captivity. Desperate to return to normalcy, she has to grapple with a son who has never known normalcy and isn’t sure he likes it. In the story’s most heartbreaking moments, it seems that Ma may be unable to live with the choices she made to protect Jack. But his narration reveals that she’s nurtured a smart, perceptive and willful boy—odd, for sure, but resilient, and surely Ma can find that resilience in herself. A haunting final scene doesn’t promise quick cures, but shows Jack and Ma putting the past behind them.

Wrenching, as befits the grim subject matter, but also tender, touching and at times unexpectedly funny.

3) "That Deadman Dance" by Kim Scott

British settlers and native Aborigines tussle over whales, disease and each other’s rights in mid-19th-century Australia.

The hero of the third novel by the Australian Scott (True Country, 1993, etc.) is Bobby Wabalanginy, a young Aborigine. His intelligence and youthful pliability make him an attractive ally to the increasing numbers of British settlers in the 1830s who are looking to establish whaling ports on Australia's southwest coast. But the alliance is uneasy: Each group suffers from a lack of immunity to the other’s illnesses, and racism is strong, particularly on the British side. Bobby bridges a few gaps by learning English, helping settlers out of scrapes and serving as a sort of right-hand-man to Dr. Cross, one of the colony’s first leaders. Inevitably, though, the detente doesn’t last: Once the kindly Dr. Cross dies, power struggles ensue among a new governor and the Aborigine tribal elders. Grimly enough, Scott's writing is at it best when there’s bloodshed: He crafts deft, exciting scenes about the visceral chaos of whaling, and a set piece in which Bobby witnesses the murder of black slaves shows how readily casual racism shifts into violence. But the book feels ungainly overall, suffering from a scruffy, episodic style that often sets particular plot changes in motion but gives them little dramatic weight. The point of view shifts often, and when the focus is Bobby, the chapters gain an even more distancing mythological sheen, making him more a symbol for the unsteadiness of British-Aborigine relations than a character in his own right. (Some scenes that place Bobby with the young daughter of the settlement's governor set up a provocative flirtation, but little is done with it.) The novel’s closing anti-rhetoric is honorable but familiar.

A few powerful scenes, but despite its research a mostly uninspiring trip to what promised to be a more dramatic era.

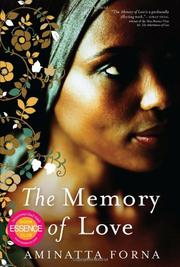

4) "The Memory of Love" by Aminatta Forna

In a soft-spoken story of brutality and endurance set in postwar Sierra Leone, three lonely men are connected by love and a legacy of terror.

Gravitas distinguishes the ambitious second novel by Forna (Ancestor Stones, 2006, etc.), which uses a handful of perspectives and consciences to consider the impact of civil war on an African nation. Adrian Lockheart, a British psychiatrist, is treating elderly, dying Elias Cole, a history lecturer who recounts his obsession, decades earlier, with Saffia, the wife of Julius, a colleague who is suddenly arrested and who dies in police custody. Although she does not love him, Saffia later marries Elias and they have a child. Was Elias partly complicit in Julius’s death? Kai, a surgeon at the same hospital as Adrian who has treated victims of the civil war, notably amputees cleaved by machetes, is haunted by terrible events. And Adrian is drawn deeper into recent history by a patient whose disorder symbolizes the scarcely bearable legacy of atrocities inflicted on the civilian population. Setting her story against a background of streets, beaches, bars, police stations and hospitals, Forna evokes a vivid social and cultural panorama. Affection between characters is overshadowed by politics, poverty and the larger fingerprint of a bloody past. While later episodes are weakened by occasional lapses of subtlety and too much connection heaped on a single character, Forna’s insight, elegance and elegiac tone never falter.

Tragedy and its aftermath are affectingly, memorably evoked in this multistranded narrative from a significant talent.

5) "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet" by David Mitchell

Another Booker Prize nomination is likely to greet this ambitious and fascinating fifth novel—a full-dress historical, and then some—from the prodigally gifted British author (Black Swan Green, 2006, etc.).

In yet another departure from the postmodern Pynchonian intricacy of his earlier fiction, this is the story of a devout young Dutch Calvinist (the eponymous Jacob) sent in 1799 to Japan, where the Dutch East India Company, aka the VOC, had opened trade routes more than two centuries earlier. But now the Company is threatened by the envious British Empire, which seeks to appropriate the Far East’s rich commercial opportunities. Jacob’s purpose is to acquire sufficient wealth and experience to earn the hand of his fiancée Anna. But his mission is to serve as a ship’s clerk while simultaneously investigating charges of corruption against the Company’s powerful Chief Resident. When a scandal involving the seizure of the much-desired commodity of copper is manipulated to implicate Jacob, he is posted to the artificially constructed island of Dejima in Nagasaki Harbor, becoming a de facto prisoner of an insular little world of rigorously patterned and controlled cultural—and commercial—rituals. Meanwhile, the story of Aibagawa Orita, a facially disfigured (hence unmarriageable) midwife authorized to study with the Company’s doctor (the saturnine Marinus, a kind of Pangloss to Jacob’s earnest Candide), punished for having aspired beyond her station, and the moving story of her planned escape from servitude and reunion with the beloved (Uzaeman) forbidden to marry her (which contains deft echoes of Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Ondaatje’s The English Patient), mocks, as it exalts, Jacob’s concealed love for this extraordinary woman. The story climaxes as British forces challenge the Dutch hold on the East’s riches, and Jacob’s long ordeal hurtles toward its conclusion.

It’s as difficult to put this novel down as it is to overestimate Mitchell’s virtually unparalleled mastery of dramatic construction, illuminating characterizations and insight into historical conflict and change. Comparisons to Tolstoy are inevitable, and right on the money.

6) "Island of a Thousand Mirrors" by Nayomi Munaweera

The Sri Lankan civil war’s traumatic effect on the island nation's people—and one family in particular—is the subject of this verdantly atmospheric first novel.

After a graphic post-coital prologue, Sri Lanka born California resident Munaweera begins her family saga in 1948, when the British leave their former colony Ceylon, where the Tamil majority is looked down on by the lighter-skinned Sinhala ruling class. Nishan and his twin sister, Mala—children of an ambitious Sinhala teacher and a laid-back doctor of uncertain bloodlines—leave their coastal village to attend university in Colombo. Free spirit Mala falls in love with another student and marries without traditional arranged nuptials. Nishan, an engineer, is deemed acceptable to marry aristocratic Visaka, the daughter of an Oxford-educated Sinhala judge, only because the judge’s expenditures while renovating his home shortly before his death have left his family financially strapped. Visaka’s mother has recently had to rent out the upstairs of her house, and Nishan does not know that Visaka marries him while pining for Ravan, one of her mother’s Tamil tenants. Ravan and his new wife live upstairs while Nishan and Visaka move in downstairs, where they raise daughters Yasodhara and Luxshmi. Yasodhara’s closest playmate and soul mate is Ravan’s son Shiva. The children live there in innocent bliss until 1983, when Mala’s husband is brutally murdered by an angry mob during increasing Tamil-Sinhala unrest. Nishan and Visaka react by moving to America, where their daughters soon assimilate. But after a college relationship ends badly, Yasodhara allows her parents to pick a husband for her. As Yasodhara’s marriage falls apart, successful artist Luxshmi returns to Sri Lanka to teach children wounded in the war. Meanwhile, in northern Sri Lanka, a young Timor girl is drawn into the intensifying civil war until her life’s destiny crosses those of Luxshmi and Yasodhara.

Compared to the expressive, deeply felt chapters about Yasodhara’s family, Munaweera’s depiction of war-torn Sri Lanka, though harrowing, seems rushed and journalistic, more reported than experienced.

7) "The Death of Bees" by Lisa O'Donnell

An unusual coming-of-age novel that features two sisters who survive years of abuse and neglect.

The story is set in Scotland, written with a distinct Scottish flavor, in very brief chapters told from the alternating points of view of the two girls and a neighbor who takes them in and ultimately covers for them when their dark secret is uncovered. The story starts when the older sister discovers both of her parents dead, her father suffocated in his bed and her mother hanging in an outdoor shed. She and her younger sister decide to bury their parents in the garden rather than risk a return to the foster care which they had previously endured and disliked. To anyone who asks, including a drug dealer to whom their father owed money, they say their parents are in Turkey, but eventually the drug dealer finds the passports the parents would have needed to travel abroad. The neighbor, who has his own secrets and heartache, looks after them, feeds them and takes them into his home. Meanwhile, the dead mother’s father, who had abandoned her not once but twice, comes looking for her to make amends since he got himself sober and discovered God. He does not, however, treat his granddaughters in a very loving way. In the midst of these developments, the neighbor’s dog discovers the bones in the garden, and the neighbor, in an effort to protect the girls he has come to love and cherish as his own children, moves the bones to his own garden and eventually claims to have murdered the pair. While dealing with this strange and surreal experience, the two girls also go through the more mundane trials of female adolescence—peer pressures at school, menstruation and the confusions that accompany awakening sexuality.

The author’s experience as a screenwriter is most definitely apparent, as the reader always hears the voices and can visualize the dramatic, sometimes appallingly grim scenes. Recommended for readers who love film.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.