1) "The Dark Between" by Sonia Gensler

Three Victorian teens in 1901 Cambridge, England, become perilously embroiled in the Society for Metaphysical Research’s deadly investigations of paranormal phenomena.

After masquerading as a spirit apparition for a charlatan medium, 14-year-old Kate Poole finds herself on the street when society members expose her employer’s fraudulent practices. Desperate and pragmatic, Kate arrives at Summerfield College, where society member Oliver Thompson discovers she’s the illegitimate daughter of his late friend and offers her a temporary job. Here, Kate meets Thompson’s impulsive niece, Elsie Atherton, and skeptical Asher Beale, son of Thompson’s American colleague. Elsie suffers from seizures, during which she sees and hears spirits of the recently deceased, while Asher’s estranged from his father and at loose ends. When several dead bodies surface on campus, raising disturbing questions, Kate, Elsie and Asher bond as they explore how far society members will go to test their theories of near-death experience. Gensler captures the suspenseful atmosphere of a time when people were obsessed with the paranormal and loosely bases many characters on historical figures prominent in psychical research during this period.

Lovers of intrigue should enjoy this lively Victorian mystery whose teen heroes experience danger, romance and ethical dilemmas as they delve into “the dark between.” (author’s note with references) (Historical fiction. 12 & up)

2) "Angels and Insects" by A.S. Byatt

Two postmodern novellas with Victorian themes that have all the leaden scholarly pretension of that era--and none of the leavening irony that made Byatt's bestselling Possession (1990) so successful a mix of erudition and wit. Taking two intellectually incompatible ideas--Darwinism and spiritualism--of the period, Byatt then sets them up in their quintessential Victorian settings, where they are observed, illustrated, and dissected like the insect specimens of the first novella and found to signify not very much, despite quotes from the greats and the Bible. In ``Morpho Eugenia,'' impoverished naturalist William Adamson, homeward bound from insect-hunting in South America, is employed by a wealthy clergyman-scholar who's trying to write a book that will reconcile his religious beliefs with his scientific interests. Adamson soon falls in love with the clergyman's daughter, the beautiful Eugenia, whom he marries only to find that her behavior is eerily similar to that of some of the insects he's been studying with the help of governess Matty. With the proceeds from his book on ants, Adamson then heads off with Matty to South America, cheered by their sea captain's thought for the day: ``That is the main thing--to be alive.'' The widow of this same captain is one of the protagonists of ``The Conjugal Angel,'' in which a group holds weekly sÇances where she is medium. They meet in the home of Captain Jesse and his wife Emily, Alfred Tennyson's sister and once the fiancÇe of the beloved Arthur Hallam, to whom the poet dedicated that great Victorian icon ``In Memoriam.'' All of which means a great deal of poetry quoted, a great number of spirits consulted, and much speculation about just what Alfred really felt for Arthur--as well as an abrupt ending in which an angel teaches all those present a rather earthly lesson. Too much learning can be a dangerous thing for a novelist who needs to separate the learned monograph from the illuminating tale. Dull and forced.

3) "In the Shadow of Blackbirds" by Cat Winters

A bright young woman is caught between science and spiritualism in her quest to make sense of a world overcome with war and disease in 1918 California.

Mary Shelley Black’s world has been turned upside down by the arrest of her father at their home in Portland, Ore. It is 1918, and the country is at war; those who speak out against it, like her father, find themselves persecuted. Mary Shelley flees to her Aunt Eva in San Diego to avoid possible fallout from the arrest and since it might be a better place to wait out the influenza epidemic that is sweeping the country. Her new home allows her to reconnect with the family of her first love, Stephen, now a soldier fighting in the war. This place is just as full of anxiety and fear as Portland, the toll from war and disease sending her families grasping at anything to alleviate their pain. Stephen’s distasteful half brother, Julius, exploits those fears and the growing interest in the occult by serving as a “spirit photographer”—an occupation Mary Shelley is skeptical of until Stephen is killed and she is visited by his ghost. Winters strikes just the right balance between history and ghost story, neatly capturing the tenor of the times, as growing scientific inquiry collided with heightened spiritualist curiosity.

Vintage photographs contribute to the authenticity of the atmospheric and nicely paced storytelling. (Historical fiction. 12 & up)

4) "The Diviners" by Libba Bray

1920s New York thrums with giddy life in this gripping first in a new trilogy from Printz winner Bray.

Irrepressible 17-year-old Evie delights in her banishment to her Uncle Will’s care in Manhattan after she drunkenly embarrasses a peer in her Ohio hometown. She envisions glamour, fun and flappers, but she gets a great deal more in the bargain. Her uncle, the curator of a museum of the occult, is soon tapped to help solve a string of grisly murders, and Evie, who has long concealed an ability to read people’s pasts while holding an object of their possession, is eager to assist. An impressively wide net is cast here, sprawling to include philosophical Uncle Will and his odd assistant, a numbers runner and poet who dreams of establishing himself among the stars of the Harlem Renaissance, a beautiful and mysterious dancer on the run from her past and her kind musician roommate, a slick-talking pickpocket, and Evie’s seemingly demure sidekick, Mabel. Added into the rotation of third-person narrators are the voices of those encountering a vicious, otherworldly serial killer; these are utterly terrifying.

Not for the faint of heart due to both subject and length, but the intricate plot and magnificently imagined details of character, dialogue and setting take hold and don’t let go. Not to be missed.(Historical/paranormal thriller. 14 & up)

5) "Distant Waves" by Suzanne Weyn

6) "Delia's Shadow" by Jaimee Lee Moyer

Ghosts and serial killers in 1915 San Francisco, Moyer’s debut.

From a young age, Delia Martin could see and interact with ghosts. After her parents were killed in the 1906 earthquake, family friend Esther Larkin took her in. Later, the persistent ghosts drove Delia to New York. She returns in 1915, ready, she thinks, to confront the ghosts and celebrate the wedding of her closest friend, Sadie, Esther’s daughter, and visit a now terminally ill Esther. But the ghosts haven’t gone away; one determined woman, whom Delia calls Shadow, needs Delia to do—something. Coincidentally, or maybe not, Sadie’s beau, Sgt. Jack Fitzgerald of the SFPD, and his superior, Lt. Gabe Ryan, are investigating a serial killer. Thirty years ago, Gabe’s father, Matthew, tried and failed to catch what appears to have been the same killer. Shadow, it seems, was one of the killer’s victims. The crimes are characterized by an insensate sadism, a taunting of the police—first Matthew, now Gabe—and an obsession with ancient Egyptian funeral rites, practices and beliefs. Poor Delia, however, is almost overwhelmed with the sheer number and power of the ghosts she perceives, so she turns for help to psychic Isadora Bobet, who not only senses ghosts, but knows how to deal with them. But can Dora teach Delia what she needs to know before the killer catches up with all of them?

The narrative is impeccably constructed and presented, almost to the point where it seems like it’s on rails, though the characters are life-sized and blessedly free of any compulsion to do stupid things in order to further the plot. What’s missing are sparks of originality to make it stand out.

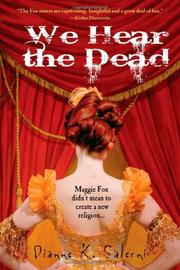

7) "We Hear the Dead" by Dianne K. Salerni

8) "The Girl in the Glass" by Jeffrey Ford

1932—hard times for most; easy pickings for flim-flammers.

But, of course, you gotta know the territory. Which, for the ladies and gentlemen of the con, means locating that apex where the swollen wallet meets the fat susceptibility. Thomas Schell, a confidence man descended from confidence men, is a dab hand at isolating the mark. His current game is spiritualism, and when deep in a “mediumistic state” he can charm the ghosts from the nether world so convincingly that he and his two trusty aides are making a good thing out of the Depression. His aids: swami Ondoo, Schell’s mystical deputy, and Antony Cleopatra, third banana, chauffeur and muscle in time of need. Ondoo, aka Diego, a young Mexican illegal befriended by Schell, serves as narrator. He idolizes his benefactor, aims no higher than to match the skills that have made Schell enviable in the con community. But the incisive, miss-nothing Schell is less than himself these days---a kind of weltschmerz seems to have undercut his transcendent amorality. It’s about this time that Schell sees, or imagines he sees, the eponymous girl in the glass and is knocked sideways by the apparition. A child is missing, he subsequently learns, her family desperate, the police baffled, and Schell, impenetrably skeptical to now, thinks he might have been given a sign. In the meantime, there are other developments to cope with. For one, Diego has fallen in love, diminishing, to a considerable degree, his ability to focus. For another, there’s the bothersome presence of a bevy of KKK-like crackpots, their mission: the racial purification of Long Island, N.Y. Suddenly, the trickster life has gone complicated.

Ford (The Portrait of Mrs. Charbuque, 2002, etc.) romps engagingly here—his Schell an intriguing scoundrel, as if Sherlock Homes had a Moriarity taint in his gene pool.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.